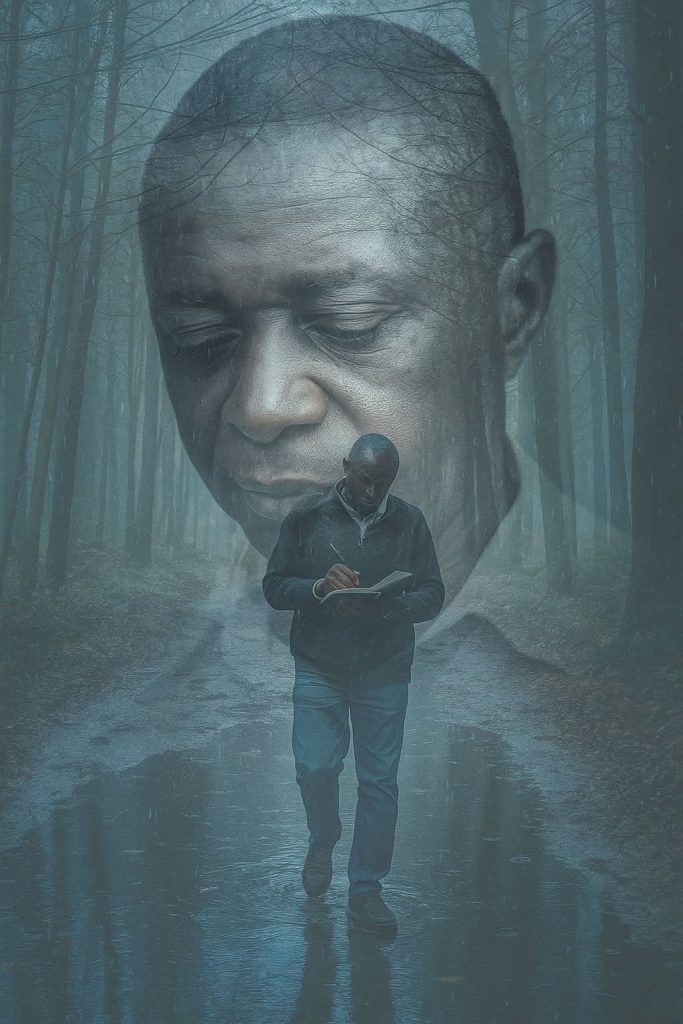

By Eneojo Herbert Idakwo

Culture and history are the twin pillars upon which every civilization rests. They shape how people see themselves, how they interpret their past, and how they project into the future. For Africa, however, the telling of her story and the interpretation of her culture have for centuries been subjected to external lenses, the lenses of colonial scholars, explorers, missionaries, and anthropologists. This has resulted in a long history of distortion, misrepresentation, and even erasure of authentic African experiences.

The time has come to demand a total decolonisation of African culture and history. To achieve this, Africa must refuse to measure her cultural heritage and historical narrative using standards alien to her lived realities. Instead, Africa must measure Africa by African standards.

The Problem of Foreign Standards

For much of recorded history, Africa’s cultural systems were dismissed as “primitive” by Western scholars who failed to understand them. African art was described as “tribal,” African religion as “fetish,” African governance systems as “stateless,” and African oral traditions as “myths.” Yet, these same societies had complex political institutions, highly advanced agricultural systems, and deeply spiritual cosmologies.

Why, then, were they so misunderstood? The answer is simple: non-African writers approached Africa from the perspective of their own backgrounds, shaped by Enlightenment rationalism, Christian missionary zeal, or colonial conquest. To them, anything that did not align with European standards of civilization was backward.

This mindset made its way into textbooks, encyclopedias, academic research, and even into the minds of Africans themselves. As Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o argues in Decolonising the Mind (1986), this process was not just cultural but psychological: it “colonised the mental universe of the colonised.” Similarly, Chinweizu, in The West and the Rest of Us (1975), insists that Africans must free themselves from the stranglehold of Eurocentric standards and reclaim their intellectual sovereignty.

The Authority Question

One of the most insidious effects of intellectual colonisation is the continued reliance on foreign authorities for “authentic” knowledge about Africa. In academic research, scholars are often compelled to cite non-African writers who produced accounts of African societies during the colonial period. But how can such works be considered authoritative when they were written from perspectives alien to the African experience?

Cheikh Anta Diop, in The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality (1974), challenges precisely this problem, demonstrating how European historians systematically denied Africa’s contributions to world civilisation. The authority to define African culture and history cannot be granted to those who were outsiders looking in. It must come from within Africa, from African historians, anthropologists, philosophers, artists, and custodians of oral tradition. Only Africans can interpret their lived realities with the depth of context, emotion, and worldview that they embody.

The Igala Experience: Debunking Revisionist Mischief

In recent years, the Igala kingdom, one of the oldest and most influential polities at the Niger–Benue confluence, has become a target of revisionist narratives. A striking example is Aminu Musa Audu’s claim that the Igala kingdom only emerged in the late 17th century through Hausa intervention, allegedly at the hands of a so-called reformer, Abu Bebeji Akono.

Barrister Usman Yakubu, in his rejoinder Revisionism and the Mischief of History, has rightly described Audu’s thesis as “disjointed and distorted.” He dismantles Audu’s claims by drawing on the works of authoritative historians such as Professors J.N. Ukwedeh, Yakubu A. Ochefu, and the late Dr. Yusufu Bala Usman. These scholars establish that the Igala monarchy predates the 17th century, with political centralisation emerging as early as the 15th–16th centuries.

Ukwedeh’s History of the Igala Kingdom c.1534–1854 situates the Attah’s authority in indigenous federations of the Igala Mela (nine aboriginal clans), which created a stable political structure long before European intrusion or Hausa migration. Similarly, Idris Ejima Aruwa (Readings on Igala people, land and language 2022) posits the Igala hegemonistic pre-dynastic monarchy era dating pre 16th century, with the igalamela in council led by the “Ajofe-Ata” with rulers like Ata-Ogu and Ata-Eri, Archaeological evidence exists today in Idah of a national monument “Ojuwo Ata-Ogu, which is the collapsed remains of Ata-Ogu’s palace. Boston’s The Igala Kingdom and P.C. Dike’s work on symbolism in Igala kingship reveal an internally evolved political and spiritual system rooted in local cosmologies.

Central to this heritage is the reign of Attah Ayegba Oma’Idoko (1614–1634), whose wars against the Jukun consolidated Igala sovereignty. Oral traditions recount his sacrifice of Princess Oma-Odoko for victory, a story deeply woven into Igala folklore. Audu’s attempt to erase this history by inserting a “Hausa reformer” not only contradicts both oral and documented evidence but also echoes colonial mischief, the kind Bala Usman condemned as “intellectual dishonesty designed to deny Africans their agency.”

Revisionism as Continuation of Colonial Bias

Audu’s claims are not merely academic errors; they reflect the same colonial logic that once dismissed African civilisations as incapable of self-organisation. By attributing Igala state formation to Hausa intervention, he denies indigenous innovation, mirroring the colonial tendency to view Africans only as passive recipients of external influence.

This is what Ngũgĩ terms “the re-colonisation of the mind” when Africans adopt alien frameworks that diminish their own heritage. Bala Usman, in his critique of colonial historiography, insisted that history must be written to empower African societies, not to belittle them. In that sense, Audu’s work recycles the very distortions African scholars have spent decades dismantling.

Measuring Africa by African Standards

The Igala example demonstrates why decolonisation is essential. Igala oral traditions, rituals, and political systems must be studied as legitimate sources of history, not judged against European archival standards. The Attah’s ritual authority, as analysed by P.C. Dike, shows how symbols of kingship encoded spiritual and political sovereignty. These traditions must be assessed on their own terms, not as imitations of foreign models.

Similarly, the integration of Hausa elements into Igala society, such as mercenary alliances during the Jukun wars, should be understood as pragmatic interactions, not as foundational interventions. African polities often absorbed external influences while retaining indigenous control, a pattern evident across precolonial Africa.

The Way Forward

1. African-centered scholarship: African historians, particularly within the aboriginal igala, must reclaim the authority to write their own narratives and not leave it to distortions and deliberately orchestrated exaggerations by writers of non-igala descent.

2. Cultural reclamation: Oral histories and cultural symbols, like the story of Oma-Odoko’s sacrifice, must be preserved as legitimate sources of historical knowledge.

3. Curriculum reform: Nigerian schools must teach Igala and other African histories from African perspectives, reducing dependence on colonial-era distortions.

4. Intellectual sovereignty: African thinkers must expose revisionist works as continuations of colonial mischief and promote authentic historiography rooted in African standards.

Conclusion

The decolonisation of African culture and history is not merely an academic exercise; it is a struggle for identity, dignity, and sovereignty. The Igala case demonstrates how dangerous revisionism can be when it echoes colonial narratives that rob African societies of their agency.

As long as Africa measures herself by foreign standards, she will remain misrepresented. But when she measures herself by her own standards, when Igala history is told by Igala voices, and African culture by African thinkers, she reclaims her rightful place in world civilisation.

To tell the African story is the right of Africans. To interpret Igala culture and history is the responsibility of the aboriginal Igala people. Anything less is intellectual mischief, and a new form of colonisation that Africa and especially the igala can no longer afford to accept.